Journalists at War

The map below is a first pass at mapping (mostly American) war correspondents involved in wars, combat zones, and major conflicts in general in which the US played a key role. I will be regularly updating it, but, for now, it is attempt to deal with several issues, the media in wars being high on the list. Each spot on the map represents a war correspondent or photo journalist. The map is somewhat dynamic in that selecting these locations provides a bit of information on the journalist and the conflict.

________________________________________________________________________

Militarist propaganda and public opinion during the Cold War

The version of the past formed by World War II and perpetuated since-the version persuading Americans that war works-has increasingly little to say. Yet even as the utility of that account dissipates, its grip on the American collective consciousness persists —Andrew Bacevich, “The Revisionist Imperative,” 2012

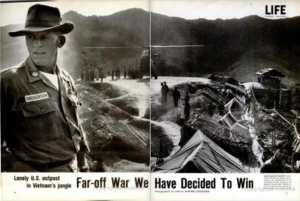

The above centerfold is from Life magazine in 1962, the first of its heavy coverage of the rapidly expanding war in Vietnam. The magazine reflected the patriotic zeal and anti-communism its famous publisher/editor, Henry Luce. Luce, as a part of his larger crusade to save Asia from communism, made use of this, his pictoral magazine, to bring the necessity of the War in Vietnam home to millions of American subscribers.

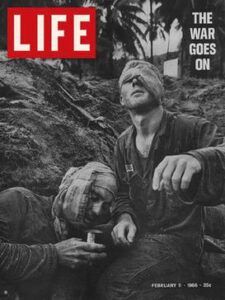

The War looked very different a few years later in 1966, as this Life cover makes clear.

In those intervening years, the American intervention in Vietnam had gone from bad to worse, and from nearly invisible at home to controversial and divisive.

……………………………………………..

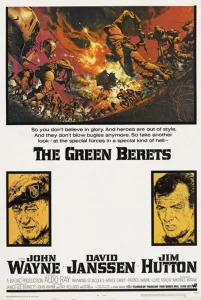

In a fit of patriotic fervor, celebrated actor John Wayne purchased the film rights to the novel, The Green Berets, in 1967 for $35,000 and never looked back. The resulting movie, differing sharply from the novel, leaned heavily on older, outdated anti-communist/Cold War tropes and conventional wisdoms around the urgency and necessity of the War in Vietnam, seemingly unaware of its own complicity in the unfolding problem. Filmed at Fort Benning, Georgia, local conditions were close enough for a mock Vietnamese village and war zone. The film’s two-dimensional characters delivered the requisite early Cold War platitudes, such as this response to a question about why the US was in Vietnam: “what’s involved here is communist domination of the world,” an idea straight from Harry Truman in 1947. Throughout, the film takes clunky shots at the news at home, at critics of the War, and assures the viewer that, quite literally, were communism to ever visit America, everyone would be “tortured and killed.” Released in the summer of 1968, the film’s plot and characters inevitably played out against the backdrop of the recent Tet Offensive and the massacre at My Lai. What was a late-sixties American audience to make of such presentations?

The whole point of this pet project had been to push back on what some like Wayne viewed as a dangerous anti-war sentiment related to the Vietnam War. Of course, the film did not turn the tide in favor of the War. While Wayne and others continued to beat the drum, they could not change the reality that had become obvious by 1968. Ultimately, the film lives in that peculiar infamy: heavy-handed and tone-deaf, the film highlighted the very problem it was ostensibly produced to solve. In this regard, the film stands as a metaphor for the Vietnam War.

What we commonly call “the Vietnam era” is understood to have been tumultuous, fraught, divisive, and inexorably tied to the American War in far away Vietnam. That War seemed to highlight certain paradoxes of the entire cold war project, both at home and abroad. While successive administrations struggled to maintain popular support amid an untenable situation, the broader public messaging in “the media” was likewise filled with contradiction and confusion. The pattern is not altogether surprising in retrospect. The War brought to forefront of American life important issues many assumed were long settled.

College, rock music & counterculture

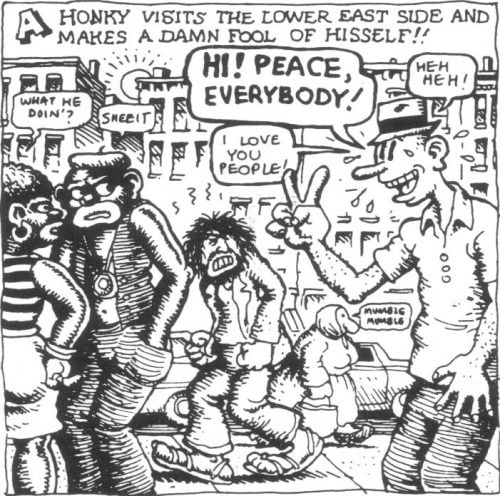

The above image is from R. Crumb, the famous (or infamous) comix pioneer of the sixties. To say that his work was provocative is an understatement. Crumb, along with a number of artists, offered provocative and satirical critiques of contemporary American society. When I found this particular cartoon recently, it immediately brought together several sometimes disparate strands–rock music culture, the counterculture, the underground press and the college campus. This cocktail has become the focus of my research lately.

A digital history component of this research seeks to map the concert itineraries of dozens of bands and artists during the latter sixties. The website containing numerous maps and related information is here: http://sixtiesrockgeo.com/

Another element of this research led me to an intriguing case study of the counterculture/hippie experience as well. By the late sixties, many especially young people began to experiment with alternative ways of living, that is alternatives to the mainstream, or “straights,” in the language common to the period. One popular alternative was communal living. Though not at all without precedent in the U.S., communal experimentation was especially provocative in Cold War America. So-called “hippies” thus engaged often drew the ire of residents of the towns/communities of which they were a part. One example of this occurred in 1968 in Madison, New Jersey, and involved a Main St. residence locals dubbed “hippie house.”

And, finally, the counterculture and the underground press flourished on hundreds of college campuses during the late sixties. The college is arguably the most important single site for these developments given the exponential growth in college student population during the decade and, as historian Theodore Roszak wrote in his classic The Making of a Counterculture in 1969, the college campus “served to crystalize the group identity of the young,”